Overview

Overview

Normal View

Normal View

2016

2016

- 2009

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

- 2019

- 2021

- 2022

- 2023

- Clear

Overview

Overview Normal View

Normal View 2016

2016

Galerie Balice Hertling

47 rue Ramponeau

75020 Paris

I – God Boxes

29 mars – 20 avril

Cette nouvelle série de sculptures, librement inspirée des Concept-tableaux d’Edward Kienholz God Box n. 1, n. 2, n. 3 (1963), consiste en des boîtes fermées de «dimensions proches de celles de l’Accumulateur d’Orgone de Willem Reich» (142 x 106 x 88 cm) et partitionnées de compositions d’objets moulées en élastomère de polyuréthane. Les structures sont en acier teinté et les panneaux, qui peuvent évoquer les bas-reliefs des portes d’églises, indiquent un intérêt pour la production sérielle, la répétition et la différence: il y a sept compositions de trois dimensions différentes, offrant autant de combinatoires possibles.

«Le seul but de ce projet, disait Edward Kienholz, est de stimuler des réflexions sur les religions organisées, ce qu’elles ont fait à la civilisation et pour elle». Ici, il s’agit plutôt de questionner les systèmes de croyances en général, le pouvoir de la représentation, ainsi que les notions de figurabilité, de fétichisation et d’ornementation–) problématiques qui sont déjà présentes dans nombre d’œuvres précédentes d’Isabelle Cornaro.

Le système de « lecture » des panneaux est construit sur plusieurs modes : linéaire (enchaînements logiques, texte et figures), symétrique (éléments ornementaux), elliptique (fragments, objets informes ou à demi-formés). Les God Boxes d’Isabelle Cornaro combinent ainsi plusieurs régimes de représentation, ressortissant tantôt à la narration, à des systèmes de correspondances formelles ou à une logique « entropique ».

Avec cette nouvelle série d’œuvres, Isabelle Cornaro opère une synthèse des questions que ses films, ses moulages en plâtre et ses installations d’objets adressaient depuis 2005, amenant sa pratique à un dialogue avec des préoccupations à la fois « classiques » (les régimes de représentation et les systèmes idéologiques qui les sous-tendent) et « modernes » (la sculpture minimale des années 1960 et l’entreprise de réévaluation des présupposés essentialistes qu’elle entreprend). S’engage, à travers ces objets, une interlocution improbable et pourtant fluide entre un Robert Morris lorsqu’il réalise sa propre version de la « Porte de l’Enfer » de Rodin, le rôle à la fois décoratif et structurel des panneaux ornant les églises baroques et la reproduction d’objets quotidiens de Fischli / Weiss…

II – Celebration

24 avril – 11 mai

«L’ombre dont la silhouette est retenue par une délinéation passe pour un élément de la personne elle-même. On reconnaitra là l’idée commune, dans la pensée magique, selon laquelle posséder une partie du corps d’un homme, ou ses excrétions, confère un certain pouvoir sur lui. Le second type de légende sur l’origine de l’art évoque l’idée que l’image remplace le mort.»

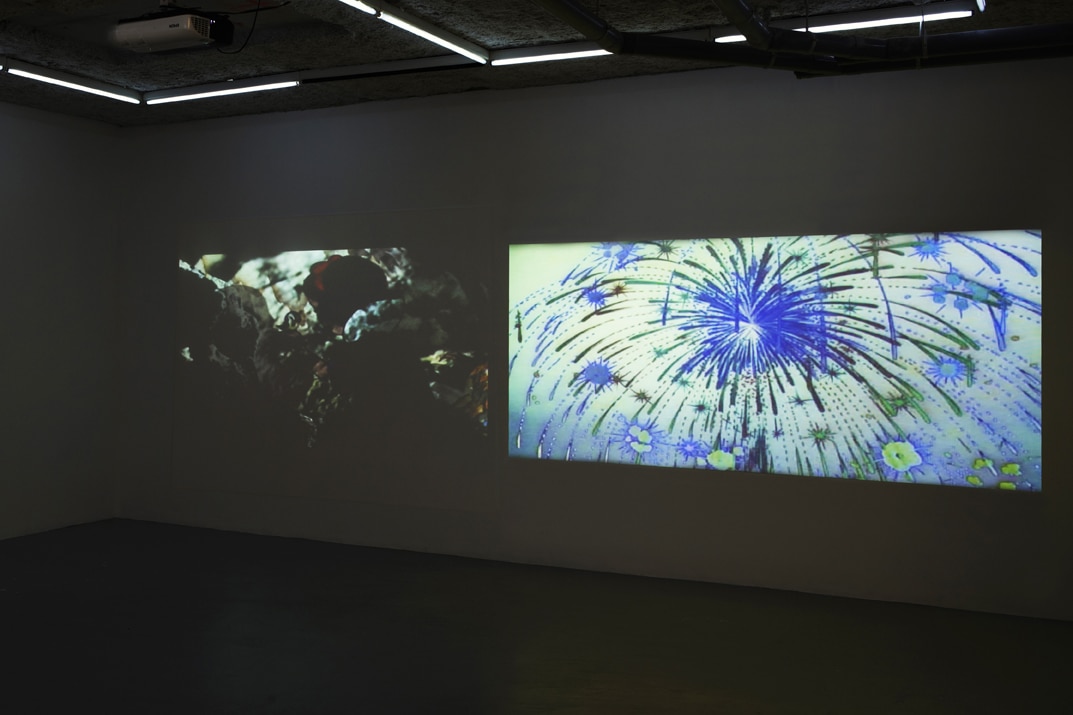

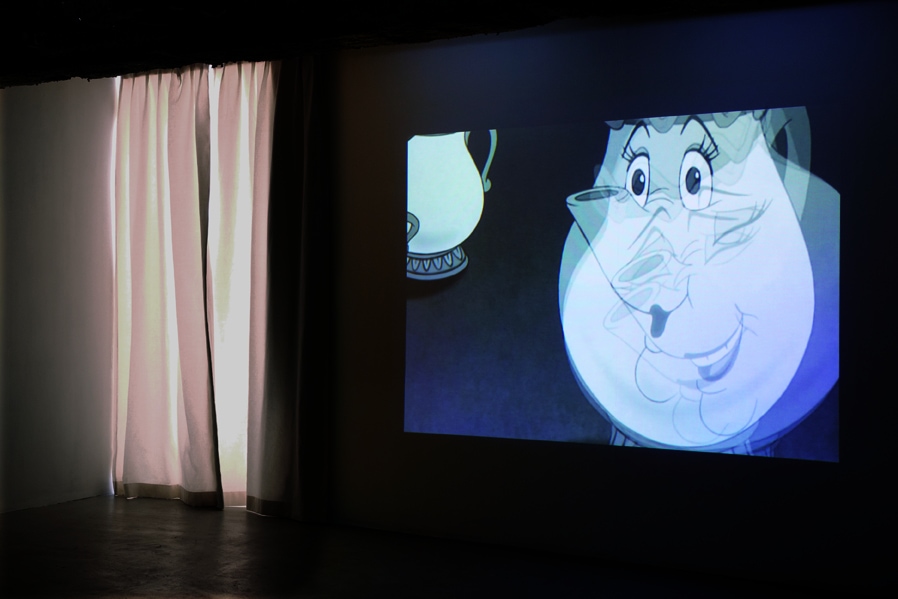

Cette nouvelle installation vidéo, d’une durée totale de 5.45 min, est un triptyque où se mélangent des images extraites d’animations de Walt Disney Fantasia, Blanche-Neige, Alice au pays des merveilles, et des images restantes, non employées au montage, des films tournés en 16mm et transférés sur support vidéo Floues et colorées (2010), De l’argent filmé de profil et de trois quarts (2010), Figures (2011). Dans les trois vidéos, les sources d’images hétérogènes sont imbriquées différemment : en succession linéaire, par superposition et incorporation, par soustraction chromatique.

Celebration montre, dans un montage rapide et systématique, des objets à valeur symbolique et économique (objets décoratifs, d’apparat, pièces de monnaie) filmés en plan fixe, avec des objets et des plantes animées de sentiments humains, dont l’hystérie est accentuée par la démultiplication des lignes d’écho à leurs mouvements rapides ralentis; le moment, colorisé par intermittences, du «meurtre» de Blanche-Neige juxtaposé à des plans panoramiques et rapprochés sur un groupe de champignons filmés en nuit américaine; des projections de peintures et de lumières colorées qui se fondent à des paysages magmatiques, à explosions répétitives.

Comme les God Boxes précédemment présentées, cette nouvelle pièce développe plusieurs problématiques déjà présentes dans nombre d’œuvres d’Isabelle Cornaro, liées aux notions de fétichisation des objets, de figurabilité, du geste artistique ; où s’opère un aller-retour du sujet à l’objet et de la forme à l’informe.

This Morbid Roundtrip from Subject to Object:

A Short Conversation Between Quinn Latimer and Isabelle Cornaro

Quinn Latimer: You’ve said of the objects you work with and cast: “They do indeed come from flea markets, which I visit without any pleasure.” This idea of pleasure, or its lack, suggests the issue of taste and distaste in your body of work. Is there a distastefulness you have for the objects you concern yourself with, either in terms of their class and/or colonial implications?

Isabelle Cornaro: The idea of taste and distaste is indeed very important in my work, as objects are chosen according to their specific sense of belon ging to a certain time and aesthetic. Namely, they come from a Western industrial culture, which by extension relates to a dominant class and the notion of (territorial) expansion—if we’re talking about colonialism. I am interested in the status of these objects in relation to the affects we invest in them. Rather than a distastefulness, it is a sort of “curious mistrust” to ward the dramatization of their origin, ancientness, rarity.

QL: What kind of affects or dramatization do you mean, in terms of the ruling class’s “investment” inthese objects—the word “investment” having both a monetary and apersonal connotation to it? And how does your mistrust translate into an attraction to work with them nonetheless? Is this connected to your interest in contesting the “naturalness” that such objects are often invested with, as you mentioned in a previous conversation that we had?

IC: The shapes and decorative patterns of flea-market objects result from a system of devaluation, which witnesses a history of forms in relation to social history. First the objects are produced as unique, highly crafted pieces; then they are widely reproduced; and finally they are standardized in a semi-mass or mass production. But the value of these objects still seems to refer to their formal proximity to an original unique model, which is seen as the “natural shape”, and which somehow became what we call “our culture”, “our tradition”.

QL: Do you consider your own sculptural works as “natural shapes” ? How does this connect to your own investment in casting them all at once, instead of bit by bit? I am very interested in your approach to nature or the natural …

IC: No, I don’t consider my own sculptural works as natural shapes. Although they may be infiltrated by existing shapes or gestures coming from both ancient and more recent art history, and thus also follow a sort of history of forms, I try to use them inside a discursive or critical movement, which hop fully creates a shift. Part of the shift lies in producing them by series, with combinatory logics and variations; this serial production implies that the subject of the work is less in the material realization of an autonomous work than in the conceptual gesture that leads its production. Also, instead of “nature” or “natural”, I would rather talk of “naturalization”. I see my work as an attempt to “denaturalize” our relationship to familiar objects, and by extension to art objects. Somehow the point is to reflect on the affective and existential construction that moves us when we deal with objects. In the end, this is an interrogation of the nature of the movement that leads a subject (a person) to invest in an object. What interests me most is this morbid roundtrip from subject to object.

QL: Speaking of trips, I’ve often “read” your horizontal cast works—the “Homonymes”, for example—as something akin to hieroglyphics. They seemed like an attempt to make sense of objects via a type of logographic writing system. What is the relationship to language in your new “God Boxes”? How have ideas of language manifested themselves in your larger body of work or been integral to your thinking about it?

IC: There is something nominalistic in the “Homonymes”, as the objects are grouped together according to typologies; they “represent” aesthetic ideas such as abstraction, stylization, and naturalism. If the structure of the “God Boxes” also revolves around linguistic notions, it is in a different way: the various panels are much more composed. They are not anymore accumulations of objects, as in the “Homonymes”, but instead exemplify different types of linguistic organizations: narrative, formal, or fragmented and elliptical. In a sense, there is a shift from signs to language, if we want to stay within linguistic categories…

QL: How does that shift take place? Does it come from the material itse lf that you are treating, or from your conceptual thinking before you ever approach it?

IC: Rather from my conceptual thinking, as the objects I use are always of the same kind. But they are employed in a different way in the “Homonymes” and in the “God Boxes”. For the former, they are taken as “what they are”: naturalistic shapes, stylized patterns, and geometric forms that reflect existing categories within art history. In the latter, the composition of the tableaux is directed by a symbolic thinking. These works tend to represent ideas I have about our intimate understanding of the world. In that sense, the “God Boxes” are much more subjective—and existential.